I just returned from a Future of Work design thinking workshop hosted by IDEO and Blue Meridian Partners in NY. An intimate and diverse group of participants, all experts in their domain ranging from workforce development to social impact investing, were taken through a set of immersive scenarios that described how work could manifest 15 years from now based on the impact of technological advancements like AI. This type of futures-thinking workshop prods participants out of their comfort zone and serves as a good tool for ideation. Similar to other future of work discussions in which I have participated, caregiving came up as a set of occupations that would persist – care for the young, the elderly, the sick, the disabled, and the community – rather than be fully automated. While on the surface, that sounds promising, Paurvi Bhatt, board member on the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers, forewarned when she appeared as a guest my WorkforceRx podcast,

“We know that the majority of people who do provide care closer to home happen to be women of color, so we’ve got this larger dynamic that’s going on where we’re trying to ensure greater levels of equity of service, employment and of fair wage. None of those things can happen, I believe, unless we reinvigorate what we can do with care at home as a true career path.”

A recent article in the Global Health section of The New York Times globalized spotlighted the issue highlighted by Ms. Bhatt: women health care workers are not compensated fairly for the long hours they put in to take care of and protect their communities. As this article showed, women in care positions are paid minimally if they are even paid at all. This article exemplifies how the narrative around community care, especially home care, should be largely free and done by largely unpaid labor borne predominately by women and people of color. (About 85% of home care workers are women, and 66% of all home care workers are people of color.)

If we are to thrive in a future care economy, we will need to change this narrative.

In PHI’s 2023 report, the monetary side of this undervaluing becomes stark. The PHI report reveals that while the population is aging and the older population is becoming more diverse, individuals are living longer with complex chronic conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and other conditions. Meanwhile, the report projects that between 2021 and 2031 the direct care workforce will add over 1 million new jobs, while almost 9.3 million total direct care jobs will need filling.

The report reads: “In the context of persistently high turnover and a historically tight labor market, home care employers are struggling more than ever to recruit and retain enough workers to meet escalating demand.”

The report found that the median annual earnings for direct care workers were only $23,688 due to part-time hours and low wages. Wages have increased slightly – just a couple of dollars more per hour – from 2012 to 2022, as shown by the report. That is abysmal and unsustainable. However, after this incremental increase in recent years, home care worker wages dropped from 2021 to 2022 when adjusted for inflation.

We see similar themes in another care field predominantly worked by women and people of color: childcare. Through the pandemic we saw how important affordable and accessible childcare is for the economy. As we come out of the pandemic and the federal turmoil calls into question the integrity of support for childcare, we are seeing how childcare (and by extension, homecare) being undervalued is hitting working women and working moms. You can’t fully commit to your job if you are providing care at home.

So, the question remains: how can we prescribe more value to these roles? As we saw in the PHI report, there are a huge number of care roles needed to fill especially as the population ages. But we can’t expect workers to want to perform them if we put a significant personal burden on the workers without valuing them.

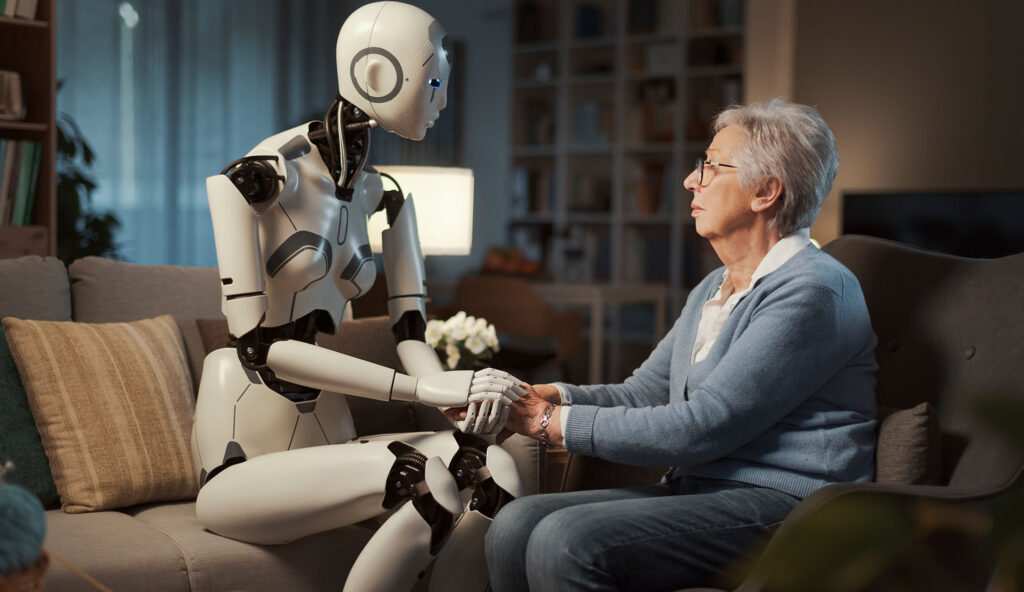

It feels like a bottleneck of all these aforementioned things coming together at once and feels like a care crisis is looming. The solution to this is accurately valuing instead of undervaluing the importance of care work. We can see the true value in the importance of care in the home as many hospitals are acting on the evidence that patients heal better at home and are sending patients to recover at home – adding more burden on the family and also inviting a different care team configuration for in-person and telehealth care into the home. The best way to demonstrate to care workers that their work is valued, is by rethinking their level of debt to train and enter into a care role and what career paths become accessible to them for attaining wage progressions. The time is now to revalue our important care workers, as the clock is ticking on who will care for us when we age.

Interested in this conversation? Visit the related readings page on our website for more thought-provoking content.

Futuro Health CEO Van Ton-Quinlivan is a nationally recognized expert in workforce development. Her distinguished career spans the private, public, and nonprofit sectors. She is a White House Champion of Change and California Steward Leader, and formerly served as Executive Vice Chancellor of the California Community Colleges.