The pandemic has wreaked havoc on the labor market, which already was in turmoil before we ever heard of COVID-19. Workers can’t find jobs. Employers can’t find workers. The current job market is the most unusual one in modern history, according to The Washington Post. Millions of Americans have either retired or are staying on the sidelines. A record number of workers quit their jobs in November 2021 and more than 10 million jobs remained unfilled, according to federal data. Meanwhile, employed workers are looking for better jobs or pay. And employers are desperate to hire.

Something has to change — and fast.

To rev up our economic engine, we need our nation to run on all cylinders, so to speak. We need to connect people with the right skills for the right jobs.

“We do not need to start from scratch,” says Van Ton-Quinlivan, CEO of Futuro Health and author of the new book WorkforceRx: Agile and Inclusive Strategies for Employers, Educators and Workers in Unsettled Times. “We can be working together in collaborative ways to build upon each other’s good works.”

Companies that need workers can’t just “‘post and pray’ that there’s a talent pool on the other end,” she adds. “There’s no more perfect time to deploy proven workforce development strategies and playbooks.”

WorkforceRx Book Launch Features Esteemed Panelists

To celebrate the launch of the book, Futuro Health convened a live panel discussion about cultivating future workforce talent. Van asked a group of longtime colleagues (who happen to be some of the nation’s leading workforce development experts) to come together and talk about how they’d search for “WorkforceRx” — what keywords they would use to find this book on Amazon, Google, or Barnes and Noble — as well as the insights, stories and strategies from the first two chapters that resonated with them the most.

They discuss matching people with the right skills at the right time, regionalization of higher education, aggregating the demand for labor and much more.

If the pandemic — along with the economic upheaval and social unrest of recent years — has taught us anything, “we’ve realized there are a lot of people who have been left out,” says Deb Nankivell, Chief Executive Officer of the Fresno Business Council.

“I think we’re in a phase in America where the business community is transforming itself into a human development, talent development ecosystem in partnership with our educators who know how to do that. Now, we all need to do ‘both-and.’ We need to learn how to get it done, and we need to know how to be inclusive and supportive of others.

The Panelists

Ophelia Basgal, Chair of the Board of Trustees, San Francisco Foundation

Ann Randazzo, Former Executive Director, Center for Energy Workforce Development

Brenda Curiel, Managing Director, Center For Corporate Innovation

Beth Cobert, Chief Operating Officer, Markle Foundation

Tom Cohenno, Principal, Applied Learning Science

David Gatewood, Dean, Shasta College

Deb Nankivell, Chief Executive Officer, Fresno Business Council

Leveraging public higher education for workforce development

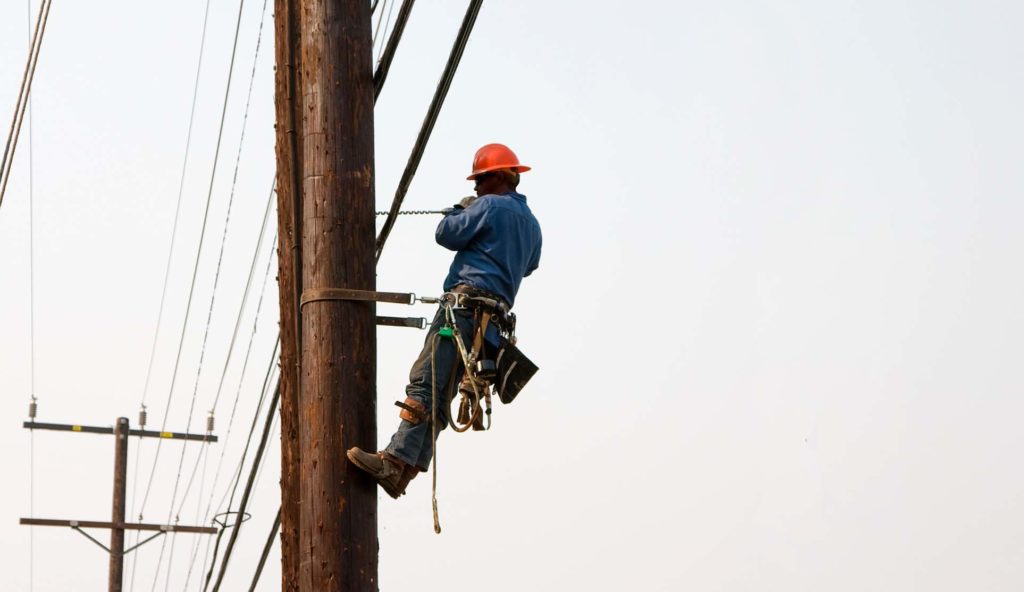

As a former executive at Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), Opehlia Bagal, Chair of the Board of Trustees of the San Francisco Foundation, saw the importance of job-specific training and preparation for high-demand but challenging roles in the utility industry.

In hindsight, it seems obvious now, but “it took Van to figure this out: asking people to climb a ladder before they became a utility worker,” she adds. “If you have to climb a 30-foot pole, you might not want to have people who are afraid of heights.”

But at the time, potential employees of PG&E would get partway through training before their acrophobia became apparent.

That resonated for Ophelia, who was working on a nonprofit-led community-build solar installation and witnessed a young man (who was recruited for the effort) climb four rungs of a ladder before he turned back and admitted he couldn’t go up to the roof.

That changed when Van created PowerPathway, a workforce development program that links industry with the California community college system and organized labor to help military veterans and underserved populations transition into energy-sector jobs.

“Van’s ability to zero in on these kinds of issues, to demonstrate what it takes to provide opportunities for employment — particularly if you’re working with the underserved communities — was just really brilliant. The success of the PowerPathway program really demonstrated that,” says Ophelia.

The talent pipeline needs to start before demand is immediate

In “WorkforceRx,” Van writes:

“I observed a key friction point that hinders education and employers from collaborating more readily. I call it the fire hose versus the garden hose dilemma. Fundamentally, employers drip out jobs like a garden hose, with one, two or three of the same jobs at most posted at a time. At the same time, education needs to have sufficient enrollees, more than just a trickle, for the college to hold a class … This type of mismatch creates timing issues for when students are ready to seek work.”

That resonated with Ann Randazzo, Former Executive Director for the Center for Energy Workforce Development, who has learned that when talent is in greater supply than employers are able to hire — or if the marketplace demands more than workers than educators can train — “programs shut down, companies look elsewhere, or students are disappointed and frustrated with the whole system.”

Ann thinks Van’s suggested fixes, which focus on collaboration between higher education and industry, are compelling. But any efforts they make “have to start before the demand is immediate,” she says. “The way to balance that supply and demand is to start early by doing what we call ‘buddy up’ — meaning that companies need to partner with others they might consider to be competitors.”

She adds: “Demand isn’t always steady, and it doesn’t always happen at the same time as graduation.”

But if companies can communicate with each other, aggregate that demand and collectively decide on their talent needs, they can anticipate (and influence) the size and skills of the potential workforce.

A pragmatic playbook for re-skilling the future workforce

Brenda Curiel, Managing Director for the Center for Corporate Innovation, echoes Ann’s insights on collaboration, adding that “multiple stakeholders are required to work together,” including “community colleges, employers, government policymakers, incentive grantors and trusted advocates deep in communities with future workers, like churches, athletic organizations, trade associations and unions.”

Brenda was in the room when Van met a chief human resources officer who was anxious about his organization’s transition to a cloud-based IT strategy. The CHRO didn’t want to fire his current engineers (who didn’t have cloud skills), and saw a lack of cloud engineers in the marketplace who he could hire within his budget.

She recalls how Van suggested a way to re-skill that company’s workers by creating the Vendor College Workplace Venture, a required skills gap certification program that “saved a lot of careers and money.”

‘Practical policies for work that work’

Beth Cobert, Chief Operating Officer of the Markle Foundation, thinks practical policies are “two words that sometimes don’t quite align, despite our best attempts.”

Through her experience with Rework America Alliance, Beth has seen the benefits of collaborations between employers and community colleges.

One such effort was an apprenticeship program for community managers in the real estate industry that brought together the Arapahoe Community College campus, the Community Association Rocky Mountain Chapter, local workforce boards and the whole community college system in Colorado. They all knew how necessary it was, but none of those institutions could do it on their own.

Beth thinks we need to ask: “How do we close these gaps? How can we create real opportunities for students, not just for their first job, but for the second job and the jobs they can follow?”

Industry-education partnerships can make a huge impact today, but “that cloud engineer you described is going to need something different tomorrow,” she adds.

A winning combination: ‘Elevated workforce collaboration’

Tom Coheno, Principal, Applied Learning Science, thinks workforce collaboration is “exactly what we need today.”

He was particularly taken with Van’s concepts of “the ecosystem of the willing” and “contributing beyond our own interest.”

When Tom worked at Southern California Edison (SCE), he recalls that the CEO received a letter from PG&E proposing a collaborative partnership, “which was unheard of,” he says. “Undoubtedly, it was a letter written by Van. We started an incredible, long-term friendship and collaboration, for which I’m genuinely grateful.”

Back then, the two utilities were on opposite sides of a big divide: different regions, different approaches to hiring. When he and his colleagues began meeting with Van, he realized that although SCE had thousands of applicants for every few vacancies, “we had no diverse applicants,” he says. “We also had a lack of geographical preference.”

Because living in Los Angeles can be expensive, it was difficult to find applicants who wanted to work there. But SCE wasn’t recruiting in L.A. or looking for people who already did.

“It was a real eye-opener and a humbling realization … the company was stuck in, to some degree, a nepotistic hiring practice — and we broke that open.”

SCE partnered with the East LA Skills Center, which provided outreach, screening and education to potential candidates. SCE contributed skilled instructors, vehicles and poles.

“In that case, Edison was contributing beyond its own interests because the graduates could go to work for any utility. They could go out of state. Nonetheless, it became almost our single source of hiring because it checked so many boxes. It worked out to be a huge advantage.”

Not only did diversity increase in SCE’s applicant pool, but the Skills Center weeded out people who weren’t great with climbing poles.

“The attrition rate dropped dramatically,” Tom adds, “and Edison probably saved the money we were investing.”

‘Doing what matters for jobs and the economy’

David Gatewood, Dean at Shasta College, says forming new coalitions and ecosystems are what matters for workforce development.

A huge, disparate state college/university system like California’s — there are 116 schools to date — hasn’t always been conducive to cross-institutional collaboration.

“The model for bringing the ‘willing’ together was clearly a change,” David adds. “I don’t know if a lot of people realized just how disaggregated we are — and independent.”

With very little hierarchical authority, the question was: How do you lead change?

The answer was to appeal to the willing, not those who resisted change. He recalls Van asking: Who are the willing? Who will join me? Who’s already doing good work? Who do we tap into?

“You did it with head, you did it with heart and you did it with hands,” he tells Van. “You did it with a vision you took out to everybody, and we worked with you to develop that vision.”

David says it took “critical listening” to create a “solidified vision of what it would take to meet the needs of the state, in terms of economic development.”

What did it take? “Braided funding strategies,” he adds. “Bringing in all sorts of different ways to support these initiatives, instead of, as Van called it, spreading peanut butter thinly at every college level, on every single career-ed program.”

Developing talent using an ‘ecosystem approach’

Deb Nankiville, CEO of the Fresno Business Council, says she and her team talk about the “ecosystem approach” quite a bit — “the idea that if you don’t address all of [a problem], you could be leaving out a key piece,” she says, likening that situation to having a flat tire on your car.

She says the “spirit of stewardship” is key to transforming the workforce as well. We need leaders “who can call out the very best of who people are, who help people remember that we have a larger purpose in our country,” she says.

Deb was inspired by Van’s story of growing up in a family of immigrants.

“To me, that is the journey of change that happens in our country,” she says. “You’re a refugee who’s looking at the past, being wounded, leaving something you didn’t want to leave, and then you become an immigrant and you look forward, see the opportunity and you move forward. Others support you in doing that.”

Another way to frame that — “something we’re working on very seriously in Fresno,” she adds — is to understand a lot of people have “severe, unresolved trauma. They were victimized, exploited. How do you shift people into confident, life-ready citizens?”

Companies and educational institutions both need to have compasses aimed at north-star goals, says Deb.

“Van has now given us the map. And it’s not just a map for people who were raised with love and support. It’s also for people that didn’t have that.”

This article is based on a special episode of the WorkforceRx with Futuro Health podcast. Episodes feature leaders and innovators sharing insights into the future of work, future of care, future of higher education, and alternative education-to-work models. Be sure to subscribe via Apple, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.